|

Down the hallway in the first floor (ďĒbasementĒ) of the MCZ, to the south of dadís cave was an enormous storage area for the ichthyology [fish] department. It looked like the catacombs, dank, dark, spider-webby places with no living people, indeed, no evidence that living people had been there in the last 50 years. I didnít think about it this way at the time, but in retrospect, I can see that Dad -bless his wrinkled hide- prevailed on Myvanway to provide summer jobs for us, jobs that OSHA -had it existed to save the poor employee- would have forbidden unless whole-body protective gear, including a respirator for clean air- was used.

I don't remember where the department offices were located but this storage area is vividly fixed in memory. Wherever it was, Myvanway hired Dick and me to do an inventory of all of the specimens stored in this area. That sounds like a minor undertaking - until you realize (a) the size of the area and (2) the number of specimens. The storage area covered half a dozen rooms that extended from one side of the building to the other, and each room was filled wall-to-wall with what can only be described as lead-lined coffins on legs with tightly sealed lids that lifted vertically.

I donít know whether this was just a make-work project for Dick and me or whether it was actually part of the annual plan for the Ichthyology department.

Whatever it was the assignment was disarmingly simple:

--Systematically work our way through each coffin in each room, and then go to the next room, until we have finished.

--Lay the lid back so that it is a storage space to lay each specimen on after we have found and recorded its tag.

--Write down the specimen number and other information on the paper tags that were stuck through a fin or chin, including genus and specie, collector, date collected, location where collected, accession number assigned by the department when adding the specimen to the collection.

-ĖPrepare a list of data for each coffin and return them to Myvanway when completed.

I donít know when the containers were built, but they were about as old as the brick walls which were built in the 1800's, hence the cobwebs and dead insects everywhere. They were lined up neatly in each room, something like 3 to a column and two or 3 columns to a room. The only windows in these musky old rooms were narrow ones lined up along the ceiling which made sense since the rooms were half buried in the ground anyway. The effect of the construction, age, cob webs, dead insects, dust and smells was that of a prison, a forgotten world where no one ever went. The latter we knew because each time we entered another room, we had to wipe cob webs off the light switches and out of our way as we walked to the bins.

These rooms, like the remainder of MCZ, had originally been lighted with gas lamps. After electricity made itís appearance, the rooms were retrofitted with wiring, fixtures and switches, but the original gas conduit was left in place, adding to the sense of antiquity. The bins were constructed of wood and stood about waist high, Heavy-duty legs supported the bins that were about 5 feet long, 3 1/3 feet across, and 2 Ĺ feet deep. To ensure that the formalin didnít get out, the containers were carefully lined with a heavy sheet of lead which had been carefully sealed in each corner. This lead shield curled up over the top edge of the sides so that there was no contact between formalin and wood.

The lids, also lead-lined, were secured with mechanisms that squeezed them down onto the bins to seal them. I donít remember what the locks were, but they required energy to loosen up when we were to raise a lid. Lifting a piece of 1 inch plywood that size from one side would be a heavy task. With the thick lead lining, it took both of us to lift and close the lid.

The fish were preserved in formaldehyde or formalin. I donít really know the difference. As far as the smell, there is no difference. They both smell bad. When we unlocked the seal on the heavy lid of a coffin and raised it, a fog of formalin rose and made your eyes burn sometimes. After the gas dissipated a bit, it wasnít so bad. Nasal fatigue, a real phenomenon we discovered, set in and we were not discomfitted any more. It took 20-30 minutes, however, to get to that state so we had to go through that irritating experience 5 days a week for the summer.

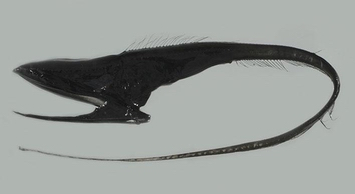

We didnít take any photos, but I pulled a few images off the internet from a Russian site for which I lost the URL. They give you a sense of the bizarre things we pulled out of the black smelly formalin. We werenít given any kind of information about what was in the bins. It was OUR job to make that discovery so when we reached down into the nasty stuff, we never knew the size of a fish we would touch, the kind, the length, the age and so on. Nothing. It was like opening a surprise every time we reached into the formalin.

This Coffinfish is interesting, but the photo shows one of the most critical parts of the collection, the documentation. Without documentation, even the most exotic specimen is almost worthless. The card tells the identity of the collector, the place the specimen was collected, including how deep, the time of day, the bait used, perhaps the temperature. Genus and specie are also provided if the collector knows them, otherwise those are left for the professional. (The photo is a modern one that has the benefit of color cards which give a reliable basis for determining the colors of the fish.) This Coffinfish is interesting, but the photo shows one of the most critical parts of the collection, the documentation. Without documentation, even the most exotic specimen is almost worthless. The card tells the identity of the collector, the place the specimen was collected, including how deep, the time of day, the bait used, perhaps the temperature. Genus and specie are also provided if the collector knows them, otherwise those are left for the professional. (The photo is a modern one that has the benefit of color cards which give a reliable basis for determining the colors of the fish.)

We learned to be careful after a few nasty little punctures. Some of these animals has evil spines and spikes that cut like razors so we had to be careful. About the best place to grab them to avoid punctures was the tail. The dorsal fin could pack a nasty sting, as could the pectoral or anal fins. Even the gill plates could be nasty. Northern Pike are a good example of the latter. The bony structures that support the pink filamentous gills are lined on the outside by heavy duty spines so if you forcefully jammed your fingers under the gill covers to get a good purchase, you were punctured by the spines which then lacerated your fingers as you dragged your finger back out.

Mouths were as dangerous because some had sharp pointy teeth that cut if you tried to pick the thing up by holding the mouth. Some fish had such long sharp teeth that if you tried to pick the fish up by squeezing on top of the upper lip and the bottom of the bottom lip, you would force the teeth through the opposing jaw and into your finger. We ran into fish like this Fangtooth with those nasty teeth. You learned to be careful anytime you grabbed onto a fish you didnít already know.

|

Here are three more examples of weird fishes. I donít remember specifically which weird ones we handled but they were as bizarre as these are. It was a great education. We slowed down to marvel at some of the things we saw. Some of them were was just amazing, as was the age and collector of some of them. We didnít know most of the individuals, but we recognized Agassiz in some.

These experiences added something to my fund of information that couldnít be acquired anywhere else, other than in a large museum.

USE SITE MAPPER TO GET AROUND

|